This is a 1997-8 article recovered from my hard disk archives and revised. Some photos are small because this was 1997 – they were very small scans on my old website.

I ordered a Martin Guitarmaker’s Connection kit a month before my wife and daughter flew from Scotland to Barbados for a two-week vacation. After years of playing dreadnaught-size instruments – an Ibanez from 1968 to 1986, then a 1981 Martin D-18 – I wanted an 000 or 0M. I’d been told it would suit my fingerstyle playing better, and some of our local professionals like John Renbourn and Tony McManus seemed to prefer the bright treble and airy bass of the slimmer body.

The new ‘Martin’ – you aren’t allowed to call it that! – Grand Auditorium kit was described as 0000 size, the same body shape as a jumbo but without the depth. I paid $370 for a rosewood body, mahogany neck with rosewood headstock trim, ebony fingerboard and bridge and an extra $25 for a coast Redwood top in place of regular spruce. (Edit: please note: the top is not redwood, it has been identified as Sitka spruce or more likely Western Red Cedar, with an unusual knot figure badly bookmatched, probably why it was available – but it is a superb top in terms of sound). With a luthiery book and air shipping it came to just under $500. (Edit: the kits are still uncer $500 in the USA!)

This was my first attempt at luthiery – well, actually at any kind of woodwork since high school, where I was deemed incapable of handling a saw or a chisel. I have no workshop, so I made the guitar in our games and music room using a Black and Decker Workmate and a full-size pool table. I had to buy some Klempsia clamps, a few drill bits, some sandpaper and wire wool, wood glue, cyanoacrylate glue, finishing polish, and a sheet of thick MDF board to cut a body-shaped template which is used as a base for clamping when glueing. All this cost around $100 more. I borrowed a router, which is needed for the most difficult part of the entire job, cutting the rebate round the body where the binding will fit.

The guitar was easily completed during my family-free fortnight. Apparently difficult parts, like glueing the two halves of the bookmatched rosewood back together with a decorative inlay between them, are easily tackled using the Workmate’s screw-operated split top bench `vise’ action. Just clamp the sheets down, and bring them together under gentle even pressure. The same vise action was perfect, with padding, for clamping the fingerboard to the neck in a single action – the usual method calls for a dozen or more clamps.

The pool table was also a great surface to work on, with its perfectly flat slate and soft baize surface! There was no risk of scratching the delicate top when working on this. Cutting out the body shape, fine sanding, inlaying the rosette and fine-carving the neck to its heel and headstock all proved much easier than I thought. The woods are of such good quality that they work with precision and you get a fine finish in hours rather than days.

I found my Dyson vacuum cleaner with fine filters useful, both to clean up after working and to remove the ultra-fine sanding dust left by 1000 grade papers from the surface of the wood. As it was summer, I did heavy sanding outdoors. (Edit: just as well, as rosewood dust is carcinogeni and I did not know that!). I only worked in the evenings and for three weekends, and spent roughly 40 hours in total building the guitar.

Luthiery by numbers

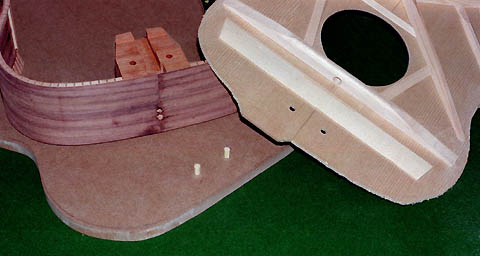

Most of the strut and tone bar shaping is already machined, the soundhole is precut and the rosette rebated. The side ribs are pre-bent, so you don’t need a steam bending jig. All structural blocks are precut. You’re working just like a real Martin luthier, starting not with the raw innards of a tree, but with a machine-cut blank that you finish by hand. You can reshape, carve and adjust all the parts as you wish. I parabola-sanded and scalloped the X-braces and tone bars respectively. (Edit: I also carved the braces and tone bars so they do not solidly attach to the top, but have defined zones radiating from the bridge, leaving two circles of the top unconstrained – I did not write about this at the time, in case it failed and made the top uneven over time. In practice there have been no problems to date – 2024).

The back is given its belly during final assembly, by sheer force. You mate the assembled front up against a rigid flat surface (the MDF template) and the back is clamped down to follow the curve of the sides, as the body gets slimmer towards the neck. This seemed the least well-engineered aspect of the guitar, but the wood glue is capable of standing the considerable tension and nothing went out of shape as a result. Martin’s instruction suggest doing this before fitting the top. Other books say differently, and I’m very glad I fitted the redwood top first, preventing any distortion of the ribs under such pressure.

My routing for the plastic binding was not deep enough, and I ended up with some very slim white-black-white purfling in a couple of places. It would always be possible to remove this, front and back, and deepen the routing before re-binding to a more robust thickness, and maybe with better material. If you can afford a laminate edge trimmer instead of a router – they are inappropriately heavy and violent for dealing with a delicate hollow structure – then buy one. A good Hitachi model capable of following the camber and curves properly is around $120.

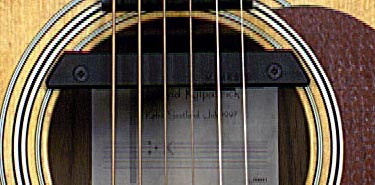

Above is my soluition good method for positioning the bridge. I used two dowel rods and marked them against my Martin which had an identical scale length.

The ebony fingerboard is supplied fully shaped and slotted for the pre-cut fret wire, and despite some difficulty with `springing’ the fretting went OK. A further $40 was needed for a fret file to turn my flat-topped frets into correctly rounded ones, but this wasn’t until after the guitar was finished and strung and had been played for a month. I used a cheap plastic saddle and kept the nut slots a little high until I the guitar had been under full medium-string tension for a while. Two ivorine nuts and one saddle blank were supplied, entirely unshaped; mother of pearl fingerboard dots are provided pre cut, and merely need inset glueing then filing, sanding and polishing flush.

In contrast to the quality of these and the enclosed machine heads, the end block plastic inset, plastic end pin and self-adhesive tortoiseshell plastic pickguard were plain tacky. So are the off-white plastic bridge pins, and in due course mine will get some rosewood ones with inlays.

The new Martin style neck strengthening rod, with tension adjustment through the soundhole, is not a good design. It demands a thicker neck D-shape if it is to sit well below the soundboard, yet Martin (in these kits as in their current guitars) have felt obliged to reduce their neck thickness compared to older models with the non-adjustable T-section strengthening bar. I had planned to reshape the neck to more of a Gibson V-shape, like my original Ibanez, as this fits my hand better, but seeing just how little wood remained between the big square trough in the neck and the outside world I left well alone.

Finishing touches

Unwilling to attempt high gloss French polishing, or use an unsuitable varnish, I copied Guild’s current style of leaving the rosewood grain open on the back and sides. I used a grain filler on the neck, for maximum smoothness, and light shellac sanding sealer on the top. A blend of button polish, teak oil and carnuba wax finished the job, leaving me with a satin finish hard enough for my own careful use and easily revived using oil and drying wax. Edit: John Renbourn signed it on top of the early coats, Duck Baker signed the bare wood… reviving the finish made John’s signature disappear but not Duck’s.

My personal touches were an initial K cut from blue sodalite gemstone and set in the headstock (very crudely!) and tan salmon–skin pickguard and end block inlay (not at all crude, and very appropriate for a guitar built on the banks of the River Tweed). Finally, after a couple of months of playing, I fitted a Martin Fishman Thinline Gold Plus active bridge pickup and a new bone carved and compensated saddle, lowered the nut action to minimum, stoned and filed the frets and added a Mimesis single coil soundhole pickup with a separate jack through the end block.

The Mimesis pickup was (1997) a very slim, graphite black unit costing around $200 (in Scotland – maybe more as an import) and hand made by luthier Mike Vanden in Scotland. You can also get a double-coil humcanceller with two EQ settings, or the Blend System with an AKG condenser mike on a flexible farm and a mix control with stereo output. Mimesis ensorsers include John Renbourn and that’s enough for me! I had listened to a demo by Celtic wizard Tony McManus before buying (if you have not yet heard Tony, you will). Edit: Fishman bought the rights to make this, and it became the Rare Earth. The guitar is now fitted with a Rare Earth humbucker, not the original single coil Mimesis.

The guitar lives in British-made Hiscox Liteflite case, costing me over $100, for three reasons – first, standard dreadnought cases won’t fit the 0000 size body and jumbo cases are too deep; second, the case weighs so little that the overall weight is about half that of my D-18 in its Martin case; third, I can stand on one leg in the middle of the flat top of the case with the guitar inside and know it won’t be damaged. Edit: in fact I made the body very slightly over 0000 or 0M lower bout width, identical to Jumbo.

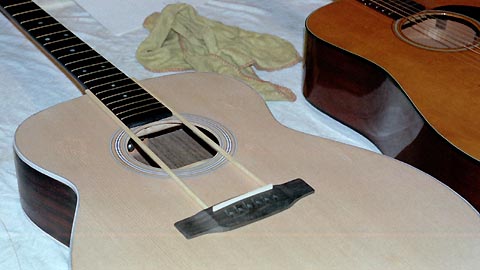

The shot above shows the guitar in 1999 next to a Yamaha dreadnaught brought in by a friend who had cut ugly notches on the soundhole for a pickup and wanted it fixing. I enlarged his soundhole as much as the inner rosette. The result was a kind of Tony Rice conversion and I’ve rarely heard any guitar as loud and clear.

Playing it

Six months on, I preferred playing my hand-made Guitarmaker’s Connection kit to my Martin D-18 – it’s simply a much more responsive instrument, lighter and with a very sweet tone and layers of resonance. The D-18 sounds robust, bassy and punchy – but the home-made has exactly that aerial quality I was looking for when playing English, Scots and Irish fingerstyle. It’s a little quiet for noisy pubs and can’t compete with the cauld wind pipes. I use a Spirit Folio Powerpad 30+30W stereo mini powered mixer (easy to carry) into two 200W boom boxes from my local CarParts4U shop ($50 each and easy to convert into superb 4 ohm stacks each with two 8″ speakers and two horns!). I often put one pickup through a Korg Pandora effects unit to add a touch of reverb, chorus or flanging while leaving the other pickup clean.

Anyway, I part-exchanged the D-18 for a Lowden S25J and now play the kit guitar all the time.

The guitar now has a signature, perhaps the first of a few – Duck Baker borrowed it to use alongside his gut-string Takamine for all his steel-string numbers when he visited one of our Scottish border folk clubs. It sounded much better in Duck’s hands than mine, even though he played it before its final intonation adjustments, and used it miked. I asked Duck to sign it, which he did. Definitely one of the good guys!

For strings, I’ve been using Dean Markley R20/80 round-cored bronze medium lights, but when photographed the guitar was strung with even more expensive Rotosound Country Gold which are piano-wound, so that the bass strings cross the saddle as a plain inner wire and the outer windings don’t start until after this – like the wound strings on a piano. They do seem to give much purer bass note with a longer sustain. (Note: this winding is called Contact Core by GHS). Edit: I now use Cleartone EQ 12s which give a very deep soft bass end as in this YouTube from the copper-bronze 6th, but having tried Martin Retro Monel 12s on a different guitar I think the brightness and punch of these would work well, and may try a set.

The only change I may make, after careful measurement, would be to take half a fretwire’s width off the fingerboard at the nut end. This would correct a common fault in guitars which don’t use zero-fret wires, making them a little harder to tune. I have a very quick tuning tuning and tempering routine which uses a sequence of octaves across all string intervals – one which I am surprised fewer players use – and it this does tend to show up this one fault. Since writing this, I have done the alteration, carefully sawing less than a millimetre off the ebony fingerboard and replacing the nut. The improvement was instantly noticeable, especially in the accuracy of octaves played using the second or third fret of any given string against its open counterpart. Edit: I did this after playing Washburn with Buzz Feiten specs and realising that a slightly ‘short’ 1st fret was important to get that intonation accuracy. In 2023 I bought a Sigma OM-T, a Martin 0000 clone in many ways, to take to travel for a festival booking in Italy, just £199 for a lightly used example from a dealer so airline damage no worry. It’s actually an exceptionally accurate guitar with much better intonation than my 1981 D18 had and I think Sigma may be taking the same approach to low nut action/1st fret distance.

Apart from that, the guitar has a slight fall-off after the fourteenth fret which would not have happened if the instructions had been a little clearer. The CNC machine cutting of the neck and block is, I suspect, so accurate now that there is no need to start shaving and shimming to produce a slight neck angle which is not necessary and causes problems with the new tension rod. Had I simply clamped the kit together as provided it would probably have been a slightly better instrument. Edit: 27 years on this seems to have corrected itself!

Martin Guitarmaker’s Connection is at 510 Sycamore St, PO Box 329, Nazareth, PA 18064 0329, phone (610) 759-2064, or (800) 247-6931 toll free from within the US. 2024: the price of a kit has barely changed! https://www.martinguitar.com/gear-accessories/parts-kits/kits/18KITR.html and you can see here very much what I received, but in dreadnaught shape. My back was not cut to shape, just two rectangles unjointed. The top was one jointed sheet also not cut to shape but with the outline marked on it.

– copyright David Kilpatrick (variant of text published in Acoustic Guitar, April 1998)